A production line of Wegovy injection pens for the Asian market at the Novo Nordisk A/S pharmaceutical manufacturing facility in Hillerod, Denmark, on Wednesday, Nov. 27, 2024.

Bloomberg | Bloomberg | Getty Images

One interpretation of the law of supply and demand is that when demand outstrips supply, scammers get busy. That’s certainly the case with the super-popular weight-loss drugs from Eli Lilly and Novo Nordisk.

As millions of Americans are prescribed injectable Ozempic and Mounjaro to treat type 2 diabetes, and Wegovy and Zepbound for obesity — and countless more without prescriptions seek them as “vanity drugs” to shed unwanted pounds — the manufacturers can’t keep up production. The GLP-1s, as they’re known, are pricey, too, and insurance often doesn’t cover them, provided consumers can find them.

That confluence of factors has laid the groundwork not only for a confusing online marketplace for compounded versions of the drugs — allowed by the Food and Drug Administration when proprietary ingredients are determined to be in short supply — but a proliferation of nefarious scams offering to sell both brand-name and counterfeit GLP-1s on websites and social media platforms.

Consumers have received Lilly- and Novo-branded GLP-1s from unauthorized sellers, counterfeit versions, completely different medications or nothing at all — other than an expensive rip-off. Most disturbing, Novo told CNBC that as of mid-November, it is aware of 14 deaths and 144 hospitalizations of people who had taken compounded semaglutide, the active pharmaceutical ingredient in Ozempic and Wegovy. It recently asked the FDA to ban the copycat drugs.

Within the past year, cybersecurity experts, consumer advocates, pharma researchers and media investigators have uncovered scores of accounts and content on TikTok, Facebook, Instagram and other social media platforms, as well as numerous websites, where bad actors have been doing business, much of it illegal or at least unethical.

In May, a joint investigation by the nonprofits Digital Citizens Alliance and Coalition for a Safer Web revealed how consumers are flocking to TikTok — which faces an uncertain future after a federal court on Friday upheld a law that would seek to ban the company in the U.S. on Jan. 19 — and other social media platforms and websites to purchase branded and illicit GLP-1s, often without a prescription. According to the report, scammers create accounts promising to sell the drugs for between $200 and $400 for a month’s supply — far below market prices — paid through Zelle, Venmo and PayPal rather than traditional credit cards so as to avoid tracking.

“Scammers take advantage of human emotion and human want, and the emotion and want now is that everybody wants to lose weight,” said Eric Feinberg, vice president of content moderation for the Coalition for a Safer Web. “It’s a perfect audience to use online to take advantage of people psychologically and emotionally.”

A common ruse the investigation exposed was sellers saying the drugs were coming from overseas and then claiming that the order was held up in customs, requiring an additional $300 to $500 payment to release it. The scammers were devious, said Tom Galvin, executive director of Digital Citizens Alliance. “They send a tracking number from a delivery service that shows you where your package is, but the tracking number is BS.” Digital Citizens shelled out just over $3,000 to purchase GLP-1s, and yet the money yielded no deliveries of the drugs.

No-delivery ploys can exact a serious financial toll on victims, but “the more scary ones are where you do get a product and don’t even know whether you can trust [it] or if it’s a valid company,” said Abhishek Karnik, director for threat research and response for cybersecurity firm McAfee.

Phishing for weight-loss drug victims

Tracking activity over the first four months of this year, McAfee’s Threat Research Team uncovered just how prolific weight-loss scams have become across malicious websites, scam emails and texts, posts on social media and online marketplace listings. From January through April, McAfee researchers discovered 449 risky website URLs and 176,871 dangerous phishing attempts centered around Ozempic, Wegovy and semaglutide, an increase of 183% compared to October through December 2023.

Karnik’s team has continued to monitor these criminal activities. “We’ve identified [a total of] 367,000-plus phishing attempts, and between May and August, the number of [risky] URLs we found increased by 135%,” he said.

JAMA Network Open in August published the results of a study by an international group of researchers who searched the global internet to ferret out websites for online pharmacies advertising semaglutide for sale. Among the 317 operations found, more than 42% were illegal, operating without a valid license, selling medications without prescriptions and shipping unregistered and falsified products. Six purchases were made, but only three were delivered.

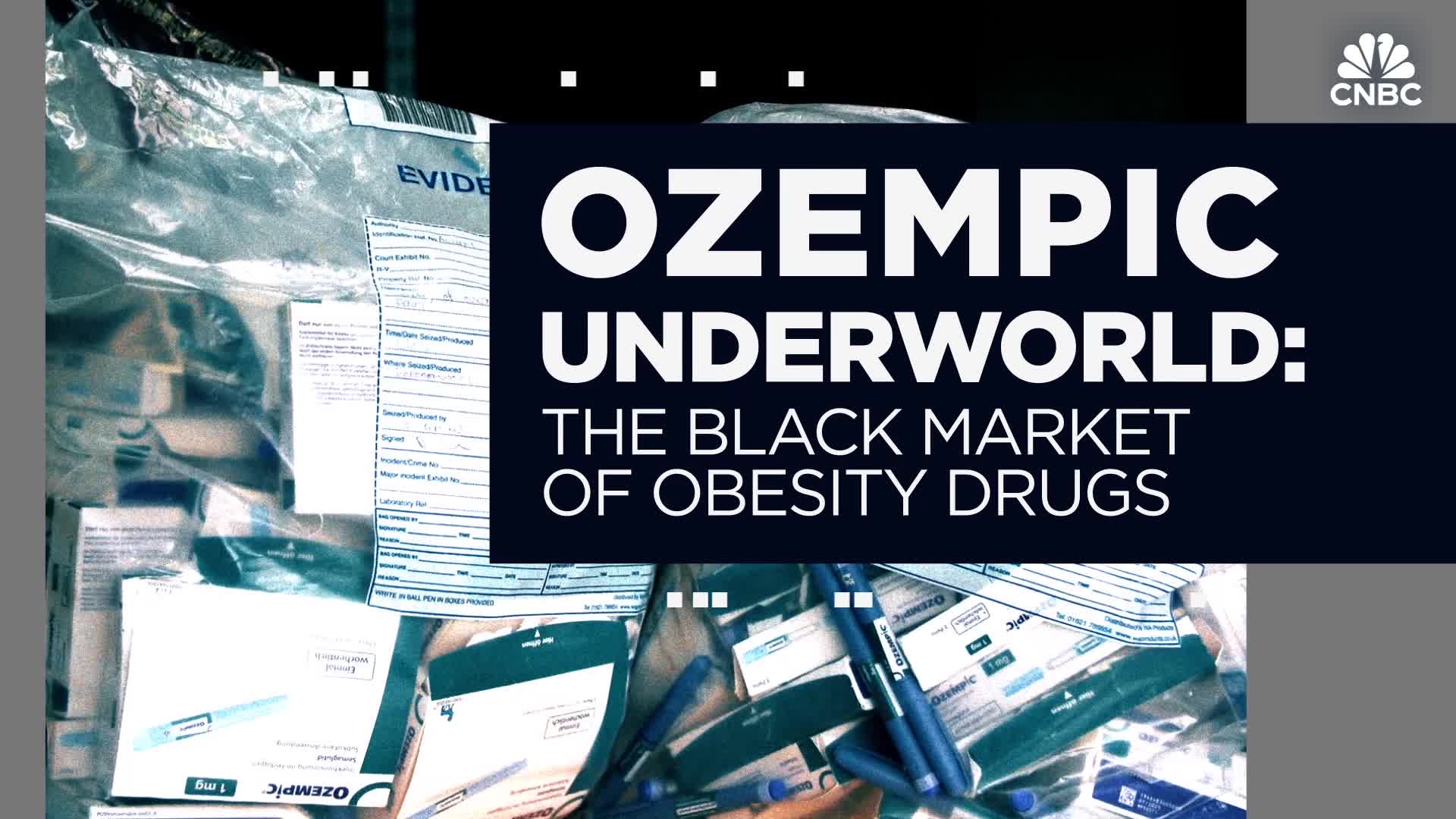

A recent CNBC investigation explored the murky international world of counterfeit weight-loss drugs. Among its findings, investigators recounted the seizure in the UK last year of hundreds of what appeared to be Ozempic pens, but were in fact insulin pens relabeled as Ozempic. They also discovered from Lilly that its retatrutide, a novel GLP-1 drug still in clinical trials and not FDA-approved, was being marketed to the public.

Counterfeits and diverted drugs — branded GLP-1s sold on the black market — originate from many countries, including India, China, the UK, Mexico and Turkey. One of the destinations where they make their way to the U.S. was New York’s JFK International Airport. According to the U.S. Customs and Border Protection, since January 1, the agency had made more than 198 seizures of products labeled as Ozempic.

In response to this glut of fraudulent activity, social media companies and web operators have employed human monitors and machine technology to identify and shut down online scammers. A TikTok spokesperson, without detailing its various monitoring efforts, referred to the company’s community guidelines. “We strictly prohibit the trade of drugs, and we do not allow attempts to defraud or scam members of our community,” the spokesperson said. “Our advertising policies also prohibit the advertising of weight-loss products, including weight-loss injections and fat-burning pills.”

Despite official policies, however, undeterred violators find workarounds when their accounts are shuttered. They might set up another account with the drug names misspelled, spaces between letters or mash-ups of semaglutide and terzepitide. Many instruct interested buyers to direct message them or send links to Telegram and other dark websites that encrypt content and provide anonymity.

“The social media platforms are the new street corners for drug dealers, and they move from place to place,” Galvin said. “It’s a game of whack-a-mole.”

Bags of counterfeit Novo Nordisk A/S Ozempic and Wegovy, foreground, and other fake drugs at a warehouse operated by the UK’s Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) in London, UK, on Monday, Feb. 27, 2024. The UK task force tracks down illegal websites, monitors social media and even carries out raids to stamp out sales of fake “skinny jabs” as both organized crime and unscrupulous lone entrepreneurs look to capitalize on the weight-loss frenzy.

Bloomberg | Bloomberg | Getty Images

For this article, CNBC found more than a dozen TikTok accounts that appeared to be selling GLP-1s in violation of its policies, including @ozempic_weightloss, @sema.irel and @semaglutideandtr. Soon after relaying the information to TikTok, we were told that all had been removed, except one, which was not in violation.

The widespread compounding of GLP-1s is another contributor to the dodgy marketplace for the drugs. In April and December of 2022, respectively, the FDA determined that semaglutide and tirzepatide were in short supply, opening the floodgates for compounding pharmacies and outsourcing facilities to manufacture, distribute and market copies, typically sold through telehealth companies, medical spas and wellness centers.

Compounded GLP-1s, unlike Lilly’s and Novo’s brands, are not FDA-approved, which means they do not undergo the agency’s review for safety, effectiveness and quality before they’re marketed. Instead, the FDA and state boards of pharmacy register, license and inspect compounding facilities and ingredients. And while some compounders meet regulatory requirements, such as Henry Meds, Noom Med, Ro and Hims & Hers Health, many others don’t.

Publicly traded Hims & Hers launched its gender-focused telehealth platform in 2017, adding compounded semaglutide to its weight-loss program this past May. “We waited until we were able to find the right compounding partner,” said Dr. Patrick Carroll, the company’s chief medial officer. Besides that partner, BPI Labs, Hims & Hers acquired another, MetasourceRx, in September. The company also sells branded Ozempic and next year will offer liraglutide, the first generic GLP-1.

FDA scrutiny

In the meantime, the FDA is investigating the bad actors in the compounding world. “Purchasing prescription drugs from unregulated, unlicensed sources without a prescription is risky,” a spokesperson for the agency told CNBC. “We urge consumers to be vigilant and to utilize tips tools from the FDA’s BeSafeRx campaign to help them safely buy drugs online.”

In May, the KFF Health Tracking Poll found that about one in eight adults (12%) said they had taken a GLP-1 drug, with about half, or 21 million, actively using the medications. Nearly 80% purchased the drugs or a prescription for them — at a cost between $936 to $1,349 per month before insurance coverage, rebates or coupons — from a primary care doctor or a specialist, according to the survey. Fewer reported getting them from an online provider or website (11%), a medical spa or aesthetic medical center (10%), or from somewhere else (2%). But that doesn’t count the inestimable number of individuals who have obtained GLP-1s without prescriptions through unregulated online channels and illicit online compounding pharmacies, many operating overseas.

While social media companies police illegal sellers of GLP-1s, hundreds of influencers are touting the drugs and their journeys using them across the platforms with impunity, according to a Fast Company report. Many influencers are recruited and paid by telehealth companies.

Meanwhile, household names have been increasingly speaking out about their personal use of these drugs, which increases familiarity and curiosity among the public. In October, People profiled 64 celebrities — including Kathy Bates, Elon Musk, Oprah Winfrey, Andy Cohen, Billie Jean King and Rob Lowe — who have talked about their weight-loss drug experiences, mostly on social media.

Currently, Lilly’s and Novo’s GLP-1s are prescribed only for type 2 diabetes and obesity. But as researchers find additional conditions that can be treated with the drugs — including cardiovascular disease, kidney disease, dementia and addiction, and most recently even knee pain — prescriptions will increase exponentially.

In September, an article in the Annals of Pharmacotherapy warned against manufacturers that use a legal loophole to sell vials containing semaglutide and tirzepatide to consumers without a prescription by stating that the drugs are for “research purposes only” and/or “not for human consumption.” The authors conducted an internet search for such scofflaws, uncovering 40 websites selling what were labeled as “peptides” to consumers.

The FDA has sent warning letters to a handful, including Miami-based US Chem Labs in February, citing several violations and requesting action within 15 days. As of Dec. 6, CNBC found that the company still listed compounded semaglutide as available on its website. US Chem Labs could not be reached by phone and an email request for comment was not returned by press time.

The authors of the Annals of Pharmacotherapy article also identified three companies that were advertising GLP-1s on Facebook, owned by Meta. “Our policies prohibit content that defrauds people by promoting false or misleading health claims, including those related to weight loss, and we remove this kind of content when we become aware of it,” a Meta spokesperson told CNBC. CNBC subsequently sent Meta the names of the three companies, and several days later their Facebook pages were removed.

Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk battle with copycat drugs

Workers walk past manufacturing equipment at Eli Lilly & Co. manufacturing plant in Kinsale, Ireland, on Sept. 12, 2024. Lilly has been bulking up its production capacity since 2020, investing more than $17 billion into developing new plants and expanding existing facilities for the weight-loss and diabetes drugs that are expected to become some of the best-selling medicines of all time.

Bloomberg | Bloomberg | Getty Images

Lilly and Novo are in a quandary regarding compounders. The copycats have filled a void while the branded GLP-1s are in shortage, attracting patients who can’t access or afford them.

But now the manufacturers want their domains to themselves. Lilly has sent cease-and-desist letters to numerous compounding sellers, and both companies have filed lawsuits against numerous compounding pharmacies, alleging trademark infringement and deceptive marketing.

On October 2, the FDA declared that Lilly’s tirzepatide was no longer in short supply, ostensibly putting compounders of that ingredient out of business. Two weeks later, though, after a public outcry from compounders’ patients and a federal lawsuit brought by compounding pharmacies, the FDA backtracked, saying it would reevaluate whether the drug is available and make a decision in mid-November.

Yet, on November 22, the FDA said it was still assessing the situation and agreed to not take action against compounders of tirzepatide until December 19, unless the agency makes an earlier decision.

Novo’s semaglutide is still listed as “currently in shortage” by the FDA, although the agency also lists Ozempic and Wegovy as “available.” A Novo Nordisk spokesperson told CNBC, “It’s important to note that availability doesn’t always mean immediate accessibility at every pharmacy. Patients may experience variability at specific locations, regardless of whether a drug is in shortage.”

Lilly and Novo have advocated for broadening insurance coverage for the drugs, and the Biden administration recently proposed that Medicare and Medicaid extend their coverage for obesity medications. Although that plan could be scuttled by the incoming Trump administration. Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., Trump’s nominee to head the Department of Health and Human Services, has suggested that obesity should be tackled through healthy eating, not drugs.

The obesity drug market volatility has shown up in recent earnings. In its third-quarter report on October 30, Lilly fell short of profit and revenue expectations, partly due to disappointing sales of its GLP-1s, even as demand for them continued to soar. A week later, Novo reported third-quarter earnings in line with expectations, strengthened by robust sales of Ozempic and Wegovy. Nonetheless, the Danish company narrowed its 2024 full-year growth guidance, reflecting, according to a statement from the company, “expected continued periodic supply constraints and related drug shortage notifications.”

Both pharma giants continue to invest billions to increase production facilities and capacity. This week, Lilly said it was investing $3 billion to increase obesity drug production at a Wisconsin plant.

Regardless, demand for GLP-1s — no matter if they’re branded, compounded or counterfeit or where they’re purchased from — is certain to keep growing. That will put more pressure on social media platforms and web operators to guard against scams.

Galvin suggested that the companies need to work together to identify scammers as they navigate between platforms to avoid detection. “Too many platforms look at this as a PR problem and not an internet safety problem,” he said. “If they were collaborating with each other to identify the bad actors and shared that information, people would find a lot less of them.”

This article was originally published on CNBC