Seen from the window of an Amtrak train, smoke billows up from power plants alongside the tracks in Northern Virginia.

Andrew Lichtenstein | Corbis Historical | Getty Images

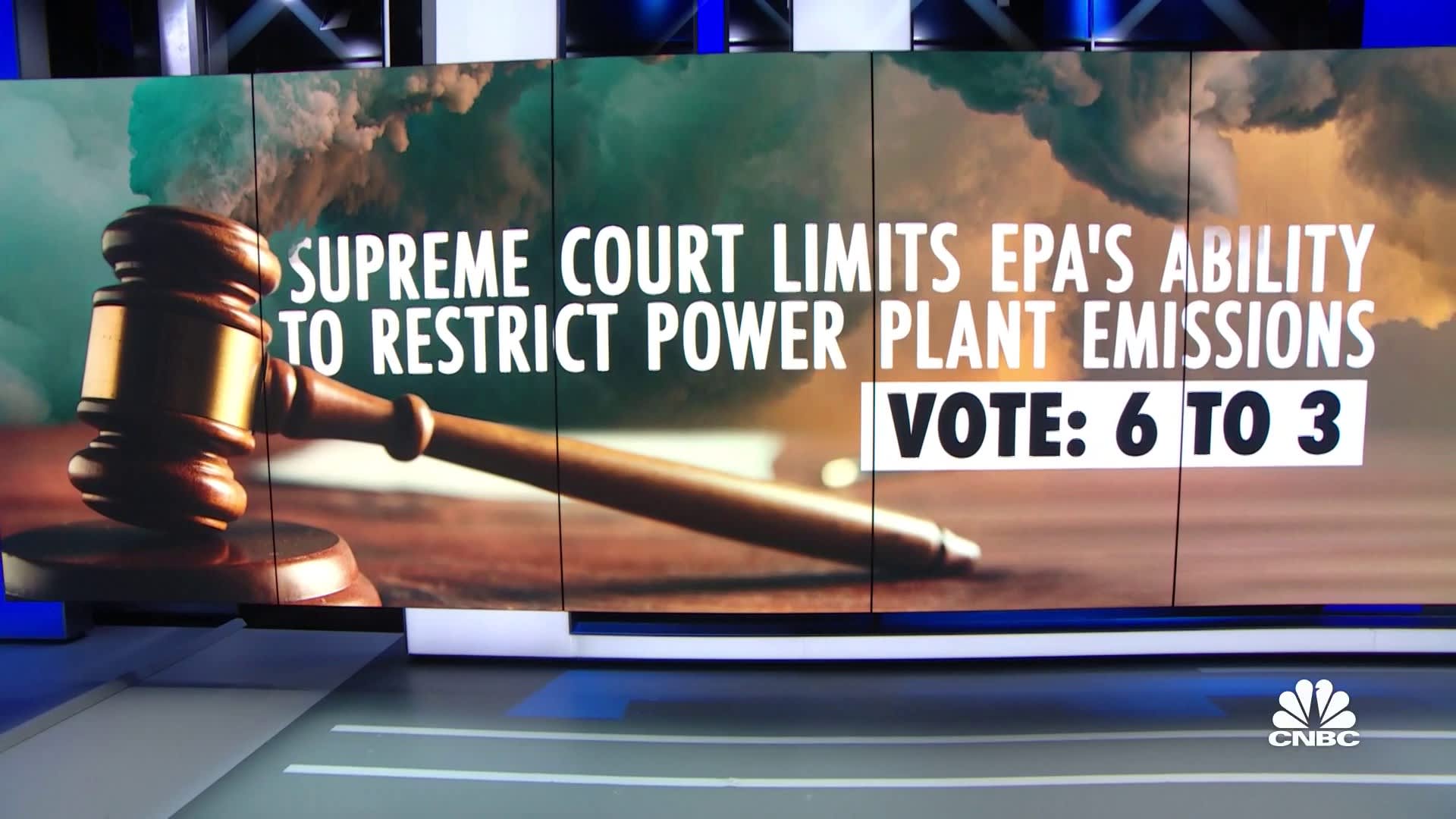

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency on Friday proposed a rule that would strengthen federal limits on industrial soot, one of the country’s most deadly air pollutants that disproportionately impacts the health of low-income and minority communities.

The proposal is the latest action by the Biden administration to better address environmental justice and air pollution. Research shows that exposure to particulate matter, known as PM 2.5, leads to heart attacks, asthma attacks and premature death. Studies have also linked long-term exposure to soot with higher rates of death from Covid-19.

Communities of color are systematically exposed to higher levels of soot and other air pollutants as they are more likely to be located near highways, oil and gas wells, and other industrial sources.

The EPA proposal seeks to limit the pollution of industrial fine soot particles — which measure less than 2.5 micrometers in diameter — from the current annual level of 12 micrograms per cubic meter to a level between 9 and 10 micrograms per cubic meter, which the EPA said aligns with the latest health data and scientific evidence. However, officials said they are also considering public comment on an annual level as low as 8 micrograms per cubic meter and as high as 11 micrograms per cubic meter.

The Trump administration had declined to tighten the existing Obama-era regulations that were set in 2012, despite warnings from EPA scientists that doing so could save thousands of lives in the U.S.

“The 2012 standards are no longer sufficient,” EPA Administrator Michael Regan told reporters during a briefing Thursday. “This administration is committed to working to ensure all people have clean air to breathe, clean water to drink and an opportunity to live a healthy life.”

If the proposal is finalized, a strengthened annual PM 2.5 standard at a level of 9 micrograms per cubic meter — the lower end of the agency’s proposed range — would prevent up to 4,200 annual premature deaths and result in as much as $43 billion in net health benefits in 2032, according to the EPA.

Some public health advocates criticized the proposed standards as not going far enough. Paul Billings, senior vice president at the American Lung Association, said the soot standards must be lowered to an annual level as protective as 8 micrograms per cubic meter in order to best safeguard public health.

“Cleaning up deadly particulate matter is critical for protecting public health,” Billings said. “Failing to finalize the standards at the most protective levels that health organizations are calling for would lead to health harms that could have been avoided, and would miss a critical opportunity to meet President Biden’s environmental justice commitments.”

Air pollution takes more than two years off the average global life expectancy, according to the Energy Policy Institute at the University of Chicago. Sixty percent of particulate matter air pollution is produced by fossil fuel combustion, while 18% comes from natural sources like dust, sea salt and wildfires, and 22% comes from other human activities.

PM 2.5 particles can be emitted directly from the source, including construction sites, unpaved roads, fields or smokestacks, or form in the atmosphere as a result of reactions of chemicals like sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxides, which are pollutants emitted from power plants, industrial facilities and vehicles, according to an EPA fact sheet.

Industries including oil and gas companies and automakers have long opposed a stricter standard on soot pollution. During the Trump administration, a slew of industry groups argued against scientific findings on the public health impact of PM 2.5 exposure and urged the government to maintain the existing standard.

The EPA is accepting public comment for 60 days after the proposal is published in the Federal Register. The agency is scheduled to release a final rule by August.

This article was originally published on CNBC